Kellyanne Conway Defends Medicaid Cuts, Says Adults Can Always Find Jobs

Reality check: Most of them have jobs already.

X

White House counselor Kellyanne Conway on Sunday came right out and said what so many Republicans are probably thinking ― that taking Medicaid away from able-bodied adults is no big deal, because they can go out and find jobs that provide health insurance.

Apparently nobody has told Conway that the majority of able-bodied adults on Medicaid already have jobs. The problem is that they work as parking lot attendants and child care workers, manicurists and dishwashers ― in other words, low-paying jobs that typically don’t offer insurance. Take away their Medicaid and they won’t be covered.

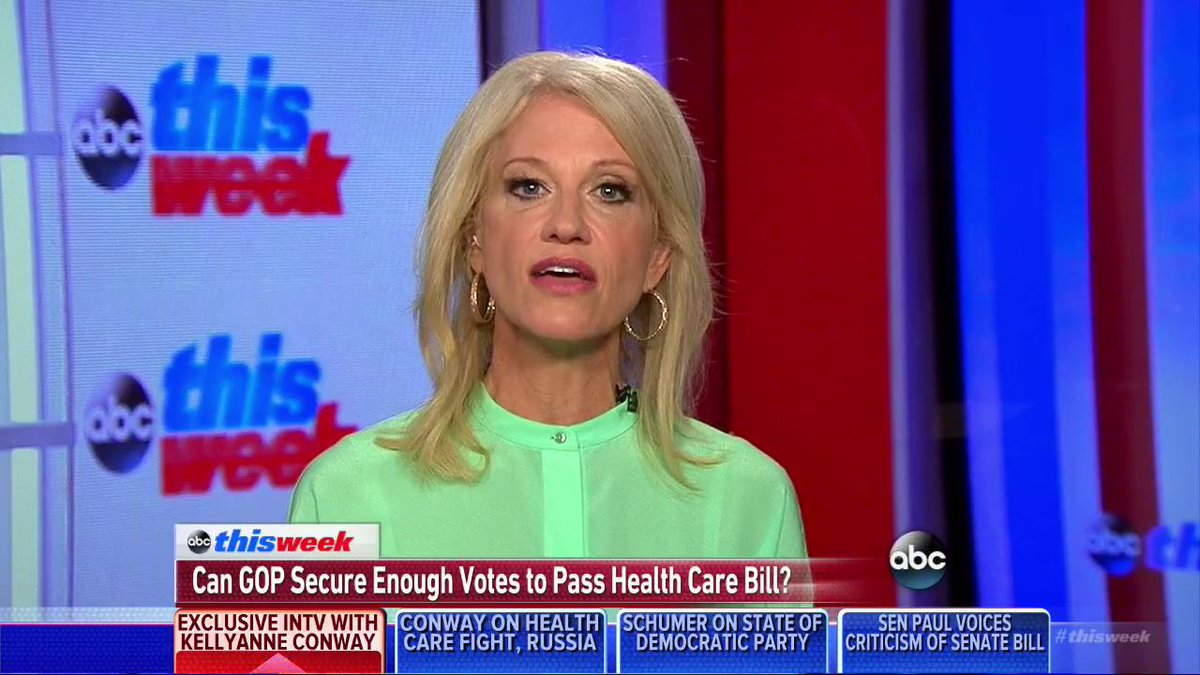

Appearing on ABC “This Week” program, Conway faced tough questions about steep cuts to Medicaid in the Better Health Care Act ― the bill to repeal the Affordable Care Act that Senate Republican leaders released on Thursday and hope to bring to a vote this week.

The Affordable Care Act ― Obamacare ― offered states extra federal matching funds to expand Medicaid eligibility, so that anybody with income below or just above the poverty line would qualify. Under the Senate bill, like its House counterpart, the federal government would withdraw those extra funds, forcing most of the 31 states (plus the District of Columbia) that accepted the money to roll back their expansions partly or entirely.

When ABC’s George Stephanopoulos asked Conway about this possibility, she offered an increasingly familiar argument ― that Obamacare had over-extended Medicaid by taking the program away from its historic mission of covering children, pregnant women, the elderly and the disabled.

“Obamacare took Medicaid, which was designed to help the poor, the needy, the sick, disabled, also children and pregnant women, it took it and went way above the poverty line to many able-bodied Americans who ... should at least see if there are other options for them.”

She added: “If they are able-bodied and they want to work, then they’ll have employer-sponsored benefits like you and I do.”

If only it were that easy.

Among the able-bodied adults that Conway and congressional Republicans have in mind ― that is, non-elderly adults on Medicaid who don’t qualify for disability benefits ― 79 percent are in families where someone works and 59 percent have jobs themselves, according to the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

The problem is that many work in low-paying, temporary, or part-time jobs that don’t offer coverage. In 2014, just 30 percent of working adults with incomes at or below the poverty line had employer-sponsored coverage available to them.

HENRY J KAISER FAMILY FOUNDATION

As for the idea that the House and Senate GOP bills would strengthen Medicaid by focusing on its more traditional populations, that claim would appear to be inconsistent with the other big change they would make.

Both proposals would fundamentally change Medicaid by ending the federal government’s open-ended commitment to providing its share of funding for the program, no matter how many people become eligible and no matter how much their care ends up costing.

Federal payments would likely fail to keep up with costs, forcing states to make cutbacks that would inevitably affect all groups that depend on the program ― very much including the disabled and elderly, whose predictably high medical needs mean their bills account for roughly half of all Medicaid expenditures, even though they represent a minority of enrollees.

When Stephanopoulos asked Conway about this, she said, “These are not cuts to Medicaid, George. This slows the rate for the future and it allows governors more flexibility, with Medicaid dollars, because they’re closest to the people in need.”

That claim, which the Trump administration and its allies in GOP leadership have made repeatedly in recent weeks, has drawn rebukes from Republican senators ― including Susan Collins of Maine, who appeared on “This Week” shortly after Conway.

“I respectfully disagree with her analysis,” Collins said.

The Congressional Budget Office has not yet evaluated the Senate bill. But when the CBO analyzed the House version of the legislation, which envisions slightly less severe cuts over time, it predicted the bill would mean 14 million fewer Americans would have coverage under Medicaid by 2026.

Comments

Post a Comment